AI Will Kill the Billable Hour

All previous assumptions about productivity per hour will become outdated.

It’s the loathed metric by which many service industries are remunerated by their clients: the billable hour. Originally meant to address the rising complexity of even simple-seeming tasks, the billable hour has become the yoke around the neck of finance departments across holdcos and independents.

The problems with the billable hour are numerous: it incentivizes the wrong things, it’s opaque and too easily allows for fraud, it pays for time and not products. A concept that has been tolerated - perhaps a bit longer than it should have - will finally meet its demise with the rise of artificial intelligence.

How Did We Get Here?

The billable hour was not the first choice of the services industry. It has its roots in law, where their infamous six-minute increments to denote one-tenth of an hour drives a level of pedantry that even this newsletter finds neurotic.

The earliest instance of someone tracking their time comes from some nerd from Harvard named Reginald Heber Smith, who began using timesheets in the Roaring 20s, tracking his work down to the tenth of the hour (or every six minutes.) This kind of practice did not become de rigour, however, until a landmark Supreme Court case titled Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar in 1975.

It all started when a young couple went out searching for a home in Virginia to call their own. As part of that process, a title examination had to be done and a licensed attorney had to do it. In a bid to increase attorneys’ income, state bar associations had put out lists of “suggested” price minimums for various items of work. The couple tried to shop around to find a lower price, but could not find a single lawyer to go below the stated price minimum.

This newsletter puts “suggested” in quotes above because in reality, the suggestion was followed up with disciplinary action by the various bar associations for those plucky attorneys willing to undercut their chondrichthyes brethren. In essence, these bar associations were acting as cartels in order to keep attorney fees (and thus their members’ income) high.

The modern-day advertising equivalent would be a group like the 4As or ANA setting price minimums for project work or AORs based on media spend, and then enforcing it by punishing those agencies willing to compete on price. This would put the agencies in quite the bind, as now a key lever of new business wins - slashing their commercials - would be gone and they would have to compete on service alone.

Goldfarb established a few things, perhaps most importantly that service fees paid to lawyers were considered interstate commerce. While this may seem obvious, one of the many arguments put forth for these services falling outside of interstate commerce (and thus outside of the Sherman Act’s nefarious antitrust mandate) was that “competition is inconsistent with the practice of a profession because enhancing profit is not the goal of professional activities; the goal is to provide services necessary to the community. [emphasis mine]” It is not clear from the court record if this was argued with a straight face.

In any event, the Goldfarbs - in addition to a new house in Fairfax County - secured a win in the highest court of the land. This type of prima facie price fixing was clearly illegal and the court told state bars to knock it off. It didn’t address, however, keeping attorneys fees high even without the mechanism of a cartel willing to (metaphorically) bust a few heads to keep everyone in line. The billable hour fit the bill.

But We Do FTEs - Not Billable Hours!

But Matt you ignorant slut - you might say - this is about lawyers, and we’re not even using billable hours anymore you dinosaur. We’re on an FTE model!

One of the refrains that could be used to push against billable hour attacks is that we don’t even do billable hours anymore as ad agencies - most of our engagements use an FTE model, where we charge per person and - except for some rare cases - don’t send billable hours for remuneration to clients.

It’s true our scoping exercises are done by the person, but the underlying assumption of those people is that they will be working 40 hours per week (or some similar equivalent based on PTO, training, and house billing.) When you’re putting 100% of an FTE on a scope, you’re putting a certain number of hours per annum there, not an actual person.

Out of the gate this drives a skewed incentive: overscope people and you can make more money and goose your margins. Do it on multiple accounts and watch the multipliers grow. Incentivized burnout begins before a name is even attached to an FTE. But that’s beside the point.

On the client side the goal is to not get overscoped, but to drive the most product out of the least amount of FTEs (and thus the least amount of hours.) This is accomplished both during scoping - when concessions are asked (or, more often, demanded) - and after the scope is signed, by asking for more work than originally discussed and hoping the agency puts it into their original hours instead of asking for more. Scope creep looks to drive as much productivity out of each hour as possible.

These things tend to be less pernicious than it may sound - it’s a game, and unless the agency is an absolute sweatshop or the client is utterly miserable (not out of the realm of possibilities, but relatively rare), the game is played with unwritten rules and strong, collaborative relationships with clients are not only possible but numerous in the ad agency world.

So Just Get Rid of the Billable Hour

Some law firms have moved away from this - the Wachtell model is well-known within the law industry and drives high fees, but also high profits, for one of the top-tier law firms in the world. But this is a rarity - Wachtell can run this kind of model because it is so elite within its industry. The majority of law firms cannot, because they are not Wachtell.

And it’s not a law firm axiom - every industry has a leader, and then everyone else. And in the cut-throat world of the advertising services industry, being unapologetically expensive - even if you can demonstrably bring the requisite value - isn’t a winning game plan. There is no forced scarcity in the ad agency world, and late-stage capitalism means commercials have to play an outsized role in awarding business.

So we remain on an FTE model, which is based on hours per annum, which correlate to deliverables and expected levels of service, which (if you have a good commercials person) translate well into value for the client. The problem is that AI is coming for this entire model in a couple of ways.

Should AI Make Agency Fees Cheaper?

Major holdcos are already seeing clients ask for discounts because of AI. The argument becomes “You’re able to do more with less, why should I be paying the same price?”

This newsletter has covered why AI should actually make agency work more expensive, not cheaper. In essence, what AI is doing is removing the rote work that has to be done, but isn’t necessarily adding tangible value to an account. That frees up time for FTEs to work on more substantial, business-driving work that our clients want front and center in the relationship. That means higher value, which should mean higher fees.

But we also tend to ignore a glaring fact about AI and how it’s used today within enterprises: it is expensive. And as money continues to pour into the industry, it certainly is not going to get cheaper. (And this doesn’t even point to the criminal aspect of ChatGPT inventing the non-profit to IPO pipeline.)

So, it follows that agency fees should actually be higher in the age of AI, given the upskilling of talent and the infrastructure resources required to run the AI that is driving the hour efficiencies.

The Formula is Broken

Which brings us back to our original thesis: the FTE model will be broken by the rise of AI in the corporate world. Given that it is based on a 40-hour work week, and that AI will drive time-based efficiencies in ways we are still trying to determine, there simply is no way to maintain the existing system without a massive imbalance occurring.

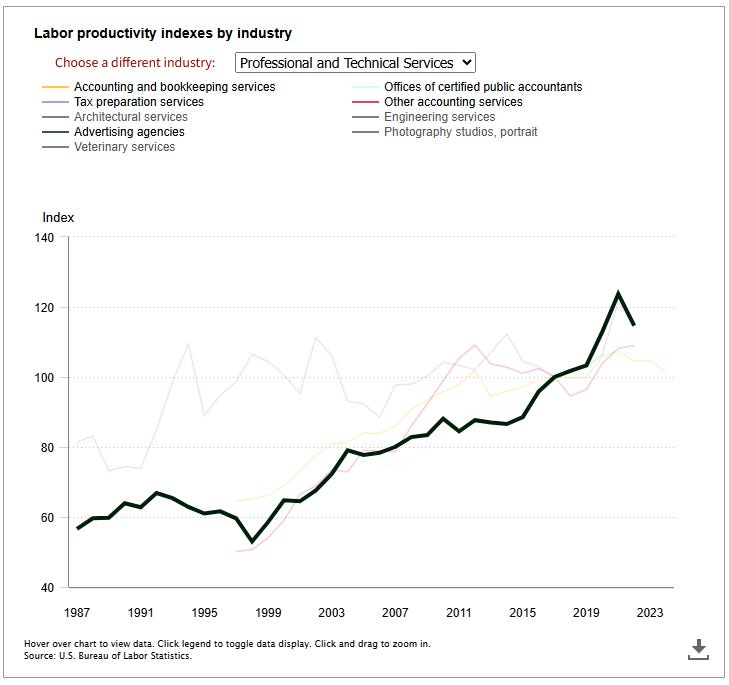

The crux of it is what is possible in the 40-hour workweek. Productivity has been rising steadily in Western economies, and the microcosm of advertising services in the US is emblematic of this.

What AI implementation across the industry is going to do is catalyze this increased productivity in ways previously unimaginable. We might not be clear on the timeline, but those who underestimate productivity gains from AI do so at their own (and their own companies’) peril.

What can be done today in a 40-hour work week will look like child’s play decades from now. Which means the value derived from the FTE model to determine agency fees needs to not only be revised, but probably thrown out and reengineered based on the coming age of artificial intelligence in our workstreams.

The expected output within 40 hours is what the entire FTE model is based on, and the FTE model is what the expected output formula is based on, and the expected output formula is what the entire ad agency remuneration process is based on. So, like when you start seeing cracks in the foundation of your home, it’s time to call in the experts to figure out how to repair this at the source, as opposed to ignoring it until the entire edifice comes crashing down.

So What’s the Fix?

The issue here is that these are entirely uncharted waters - the only thing that has been tried and worked in the past in terms of agency fees was a percentage of the client’s media spend, but that was also during the heyday of television when the cost per GRP allowed this to be a workable model for both client and agency. With the rise of the internet and programmatic buying methods driving down working media costs, the previous model would not be sustinable for agencies while remaining palatable to the client.

Maintaining the FTE model - while the least disruptive - will also prove challenging. Productivity with AI will increase, but we’re not sure by how much, and we’re not sure when productivity will stabilize to a point where the industry can settle into a relatively firm value equation off of a 40-hour work week. Making this a moving target from MSA to MSA will prove chaotic at best and downright ruinous for the industry at worst.

There is a model that has been tried in the past, but no one has quite nailed it in advertising: the outcomes model. You’re a retailer who wants to increase your same-store sales by 10% YoY? Here’s our price for that. Want to drive your NPS score up 15pts in three years? Here’s what that will cost. Need to overtake your main competitor and go from challenger brand to market leader? The MP on that dish is *quiet murmuring to avoid sticker shock.*

You get the point. The problem with this is that too many external variables exist to nail this down in a legal contract. Imagine having this kind of deal with a tech company in March of 2000, or an investment bank in September 2007, or a hospitality company in March of 2020. How do you write these into contracts beyond the force majeure language that, quite honestly, is only going to lead to litigation in this setup?

Even ignoring catastrophic events (which feel much more frequent, of late), there’s also plenty of companies out there for which marketing efforts only make up a small proportion of their revenue, at least in the short-term. These contracts would not only have to align on a way to measure the outcome of immediate marketing activity (a much thornier proposition, as anyone who has worked at a large ad agency knows), but they would also have to quantify the value of a brand, which is disproportionately fed by marketing that - on paper - has little immediate return on investment. This would lead them down a path that no one has quite cracked, given it’s trying to quantify an intangible.

Just like most of the problems clients approach agencies with, there is no simple fix. But a constant refrain I tell teams I lead is that if it were easy, everyone would do it. The lack of clarity around a short-term solution to this problem is juxtaposed by the fact that it is very clear that something will need to change. Those agencies and companies that begin down that uncertain road today will be lightyears ahead of their competition when the wider productivity picture begins to finally come into focus (kind of like it was with the AI technology causing this seismic shift in the first place.)

Grab Bag Sections

WTF Local Politics: I live in a pretty small town (just over 13,000) and in a smaller village within that town (under 6,000.) We’re in the midst of election season, and it is heated. We’re talking every tiny little thing being dissected for any political angle, personal sniping all over Facebook groups between neighbors, townfolk online calling residents who attended the No Kings rally “retards.” It’s quite ugly.

And yet, there’s the notion that we’re a small, tight-knit community and we’re all in it together in off-election years. But time and again (at least since I’ve lived here), people’s true colors come out, and they are just nasty to each other during election season. I find this extremely odd, given that I have seen the same people posting vitriol against a neighbor under their real names and profile pictures then shopping at the local grocery store and socializing with other residents, as if their online persona existed in a vacuum.

Since Covid I’ve anecdotally noticed that people are simply shittier to each other. We haven’t shaken off the self-reliance we were forced into during lockdown, and it has decimated the social contract. Having a president whose nihilism is only excepted for his grifting as the leader of our great nation has only accelerated this. And I believe the current election rhetoric in the little Pleasantville just north of the Bronx that I’ve decamped to is a microcosm of that. When Tip O’Neil said “All politics is local,” he didn’t mean that we had to stoop to the lows coming out of Washington at the national level. Yet, like many aspects of what O’Neil was fighting against in the 80s, we’re paying the price today.

Album of the Week: Have you ever listened to an album and felt that you were staring into somebody’s soul? Like the artist walked into a studio, had absolutely nothing to lose, and just let it all out into the microphone? That’s the feeling one gets when listening to Lyfe Jennings’ debut studio album Lyfe 268‒192.

Lyfe’s story is one marked by prison. As a teenager he was sentenced to a decade for an arson charge that had resulted in the death of a mother of six when he and his friends had firebombed the wrong house looking for some rival drug dealers. As soon as he got out - after teaching himself songwriting and the guitar while locked up - he hit the amateur circuit - crushing Amateur Night at the Apollo and various NYC open mikes. That led to a deal with Sony, which led to the platinum debut album.

There are few skips on it, which is rare for 15 tracks with a runtime of over 50 minutes. It hits on hard topics that don’t lend themselves well to mainstream appeal, which speaks to Jennings’ talent to be able to go platinum talking about the potential pitfalls of dating women with children (“She Got Kids”), a partner cheating but getting away with it (“Hypothetically”), and a baby momma squeezing him for child support while also being comfortable on welfare (“Greedy.”) That last one does not age well, which puts Lyfe in pretty good company from the mid-aught rap and R&B scene when it comes to misogyny.

Some standouts are the back-to-back “26 Years, 17 Days” and “Made Up My Mind,” where Lyfe laments the judgement he receives from fellow Christians upon his release from prison and how he turns to god outside of organized religion because of it. “Must Be Nice” talks about finding that special someone who sees through all the short-term fame. “Cry” - following a theme of the era - speaks to the beauty in the vulnerable. The stanzas “See cryin’ is like takin’ your soul through the laundromat / It’s like the feelin’ that you get / When you see your grandmama smile” made even this newsletter’s curmedgeon author stop and reflect.

Unfortunately, while Lyfe has put out a couple more solid albums, he never quite recreated the success of Lyfe 268-192. His career came to an abrupt end after an incident in Smyrna outside Atlanta, after a domestic dispute led him to popping off a couple of rounds and fleeing the scene in his ‘Vette. After crashing it in a police chase, he pled guilty to a slew of charges and was sentenced to another three years and change in prison. While he is out now (and relatively active on his Instagram), the hit to his career has proven to be lasting, which is too bad as his talent was and is obvious.

If you’re looking for good storytelling from a wildly talented musical artist (Lyfe wrote and produced nearly all of the tracks on the album), then Lyfe 268-192 is worthy of a spin this week.

Quote of the Week: “You want to know how super-intelligent cyborgs might treat ordinary flesh-and-blood humans? Better start by investigating how humans treat their less intelligent animal cousins. It’s not a perfect analogy, of course, but it is the best archetype we can actually observe rather than just imagine.” –Yuval Noah Harari

Usage of AI in This Post

I used one of the LLMs for deep research on billable hours (honestly cannot remember which one,) and that put me on to some articles about the Goldfarbs looking for a house. Beyond that, the other research that went into this was the old-fashioned book reading and Googling type.

See you next post!